Today, we know Unearthed Arcana as a series of digital playtest releases, but before that, in earlier editions, the name was used for additional rules and optional systems. Over the years, it has become synonymous with D&D’s experimental side, new classes, variant mechanics, and unusual ideas that pushed the game’s boundaries. It was in the original 1st Edition Unearthed Arcana that players first officially saw the Barbarian, and in 5th Edition, it’s the only place we’ve seen the Psion or the Mystic.

1st Edition and the Original Unearthed Arcana

Nowadays, when people refer to D&D editions, they often use terms like “1.5e” or “2.5e”. D&D has always evolved between major editions, adding rules and options after the core books were released. The first time this happened was in 1st Edition, with the book that gave its name to this entire tradition.

Written by Gary Gygax and published near the end of the edition’s lifespan in 1985, Unearthed Arcana expanded the AD&D rules with new classes, races, and systems. One of the biggest changes was the introduction of the Cavalier, a new base class, and the redefinition of the Paladin, which was originally a Fighter sub-class in the Player’s Handbook, as a sub-class of the Cavalier instead. The book also added the Barbarian, a new Fighter sub-class, and the Thief-Acrobat, a Thief sub-class.

In 1st Edition terminology, “sub-class” didn’t mean a specialization or archetype like in modern D&D. It referred to a full class derived from another, sharing its general framework but with distinct rules and abilities.

The Ranger, which had already existed in the Player’s Handbook as another Fighter sub-class, received an update here as well, refining its abilities rather than reintroducing it entirely.

Unearthed Arcana also expanded racial options, introducing subraces like Drow, Duergar, and Svirfneblin. Some of these loosened or removed the strict level limits that defined 1st Edition character progression. And, in true experimental fashion, the book even introduced a seventh ability score: Comeliness, derived from Charisma, representing physical attractiveness. Comeliness came with strong modifiers and detailed effects, ranging from hideous to supernaturally beautiful, extremes only possible for magical or divine beings.

Second Edition

For 2nd Edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, there was no book or product called Unearthed Arcana. However, several late-edition supplements greatly expanded the core rules, and changed the game even more than UA had in 1st Edition.

These were the Player’s Option books: Combat & Tactics, Skills & Powers, and Spells & Magic. Alongside them was a Dungeon Master Option book titled High-Level Campaigns. Technically, that was meant to start its own series, though only one volume was ever released.

I won’t go into detail about their contents since they weren’t branded Unearthed Arcana, but conceptually, they filled the same role: experimental rule expansions that pushed the system beyond its original boundaries. Because of these books, players today often refer to this late stage of AD&D as “2.5 Edition.”

The Return of Unearthed Arcana in 3rd Edition

In 3rd Edition, Unearthed Arcana made a return, this time as a full hardcover book released in 2004, about a year after the launch of 3.5 Edition. Interestingly, 3rd Edition is the only version that officially used a “.5” in its branding, but in practice, the gap between 3.0 and 3.5 was much smaller than the gap between 3.5 and Unearthed Arcana. That alone shows how experimental this book was.

One of the most popular variants in the 3.5 Unearthed Arcana is the Spell Point system, which lets spellcasters use a pool of points instead of spell slots, more like a traditional mana or MP system seen in JRPGs.

Personally, the rule that catches my attention the most is Gestalt characters. When I played AD&D 2e, our characters were often multiclass, but that system worked differently. In 3e, Unearthed Arcana’s Gestalt rules feel like an attempt to bring back that older style of multiclassing, though in practice it makes characters incredibly powerful since you’re leveling up two full classes at once.

I don’t think anyone ever called this book “D&D 3.75,” and honestly, I’m not sure how many people used it beyond the Spell Point rules. It was more of a design sandbox for advanced players and DMs who liked experimenting with the system’s structure rather than a mainstream expansion.

4th Edition and the Beginning of Open Playtesting

4th Edition also didn’t have a product called Unearthed Arcana, which means even-numbered editions seem to avoid it, so maybe 6th Edition won’t have one either, lol. But jokes aside, this is actually where the idea of Unearthed Arcana as we know it today began: public playtesting for new D&D content.

The 4th Edition core books were released in 2008, and starting around 2010, Wizards of the Coast began publishing experimental material through D&D Insider (DDI), their online subscription platform. These were digital articles that included class builds, powers, and mechanics in testing, the first real step toward open feedback and iterative design for D&D.

This is the edition I know the least about, because by then I had already switched to Pathfinder, then gone back to 3.5, and eventually to 2e again, all to avoid playing 4e.

What I do know is that 4e later received a set of revised core books called Dungeons & Dragons Essentials, which many players consider “4.5e.” However, those weren’t part of the playtest program or connected to Unearthed Arcana. They were a reintroduction of 4e’s mechanics aimed at simplifying the system, and honestly, that’s a topic that probably deserves its own post, just like many of the other things mentioned here.

5th Edition and the UA We Know and Love*

After the unpopularity of 4th Edition, Wizards of the Coast decided to hold an open playtest for the development of D&D 5th Edition. The playtesting program was called D&D Next, and it involved hundreds of thousands of players around the world. I think it was a huge success because, despite being a big fan of older editions, I consider the 5.0 rules brilliant. It just goes to show that when you have access to playtesting done by tens of thousands of your fans, you should use it, instead of rushing development based on the closed ideas of a few executives who may have never even played D&D.

The 5e core books were published in 2014, and a few months later, in February 2015, the first Unearthed Arcana document was released with experimental content that could later appear in official products if it tested well. In this first UA for 5th Edition, we saw an early version of the Artificer, which at the time was presented as a Wizard subclass rather than its own class. Over the years we have also seen concepts like the Mystic and the Psion, which have not yet appeared in published books, though many players still hope to see them return someday.

During the life of 5th Edition, more than 60 Unearthed Arcana documents have been released, averaging about one every two months. In practice, the schedule has varied widely, with periods of rapid releases followed by long gaps with no new UAs at all.

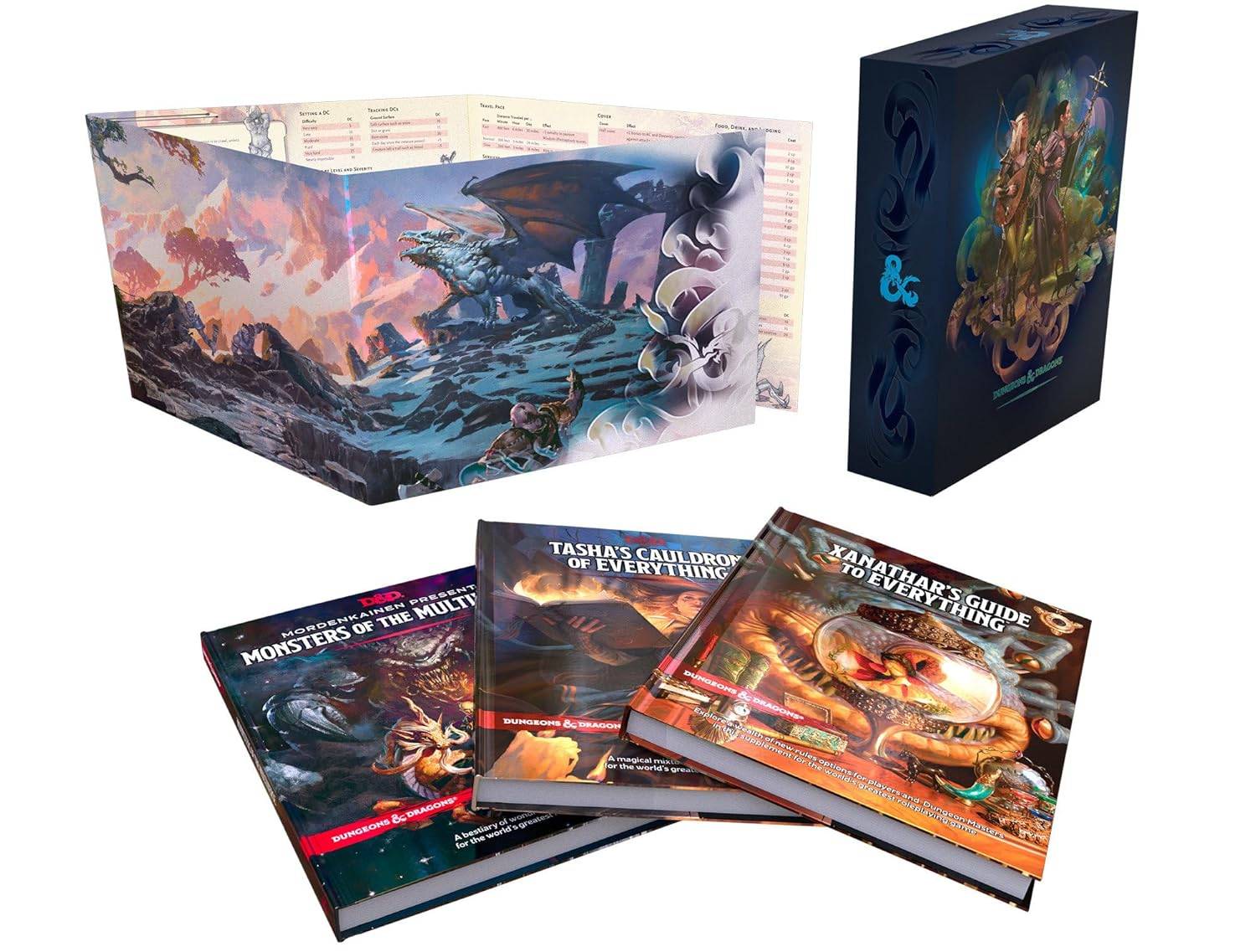

Many of the earliest UA options were later included in Xanathar’s Guide to Everything and Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything, two of the most popular 5e expansions. Wizards eventually released these together with Mordenkainen Presents: Monsters of the Multiverse in a bundle called the Rules Expansion Gift Set. At the time, many players called this set “5.5,” but now that Wizards has released a new version of the core books without calling it 6e, and the community has adopted the “5.5” nickname for that instead, people have started referring to the Rules Expansion as “5.25.”

In future posts, I would like to share my observations and opinions on the Unearthed Arcana documents that have been released recently, as well as any new ones that appear. That is why I decided to start with this short overview of what Unearthed Arcana is and how it has evolved, in case anyone is not familiar with its history.

*Ok, we do not always love the UA.